As I emerge from a self-imposed "holiday" from social media and a summer of fruitful reading, I am wrestling with a challenge that could be termed as a marketer's search for meaning.

With many parts of our society in shreds due to politically-mangled responses to the global pandemic (no doubt influenced and undermined by the cesspool of uninformed noise on social media), as marketers of our businesses, we have a role to play in mending and strengthening the fabric of society.

Small businesses keep society ticking along; hardly a day goes by that we don't use the products or services of a small business or rely upon them when venturing out and about.

We all serve a number of purposes beyond just keeping the cashflow healthy.

As your marketing advisors and consultants, you'll find that we will always encourage you to think deeply about how you benefit your customers and the community around us.

For example, in our Digital Marketing From Scratch workshop, we ask you to consider how you can be of service as a viable business, by crafting and sharing helpful content that solves problems, ideally on three levels:

- Content that solves customers' problems

- Content that makes customers feel good about themselves

- Content that solves a need or problem in society as a whole

At the beginning of 2022, these considerations seem to be more pertinent than ever before.

Imagine how different this approach is, compared to the various social media gurus out there, and the one-click tools being advertised, that promise they'll help you create a cascade of search word-rich, air-brushed, glib, and pretty social media posts, automatically crafted and scheduled for "your audiences"?

Do we need more of these "empty calories" in our social media streams?

I say, no, we don't.

So, what should we do. I certainly don't have all the answers to this malaise but I can share some insights from three books that all overlapped through sheer happenstance in my summer reading pile. I hope they give you some nourishing food for thought.

The books in question are:

Four Thousand Weeks: Time and How to Use It, by Oliver Burkeman

Man's Search For Meaning, by Viktor Frankl

The Imposter Cure, by Dr Jessamy Hibberd

As an interesting aside, Burkeman references Frankl in his book, and Hibberd references Burkeman. It's little wonder these books worked well together as a trio.

One other note before we start. This article might sound like I'm preaching. I'm not. I'm writing this for me as much as for you.

Four Thousand Weeks: Time to make decisions

This book by Oliver Burkeman is an unsettling read.

His key point is that we need to stop fudging the issue and imaging there'll be a way to live forever, and just agree that life is short and we need to make do with the 4,000 weeks (or thereabouts) that we get to strut this planet.

Burkeman's thesis is that if you scratch a little below the surface, you'll find that most of us spend most of our time replaying the past or fretting over or waiting for the future, with a great sense that we're still in some kind of dress rehearsal.

The average human lifespan is absurdly, terrifyingly, insultingly short. But that isn't a reason for unremitting despair, or for living in an anxiety-fuelled panic about making the most of your limited time. It's a cause for relief. You get to give up on something that was always impossible - the quest to become the optimised, infinitely capable, emotionally-invincible, fully independent person you're officially supposed to be. Then you get to roll up your sleeves and start work on what's gloriously possible instead.

That's quite a quote and there's a lot of background covered in the book to explain it but, in short, Burkeman's argument is that once we accept we cannot possibly do everything, we can learn to use the word "decide" to the fullness of its Latin origin.

The word, "decide" comes from the Latin de- (meaning "off") and caedere (meaning "cut"). This means that when we decide something, we're actually cutting off all the many (infinite) alternative options.

This is where he argues that all the time management gurus have gotten it so wrong; they promise that with some tricks here and there you can have and do it all. To Burkeman, that nonsense sits in the same box as the myth of "work/life balance" which really just adds extra stress about worrying whether we're being properly at work and properly not at work in some quest to be a super human.

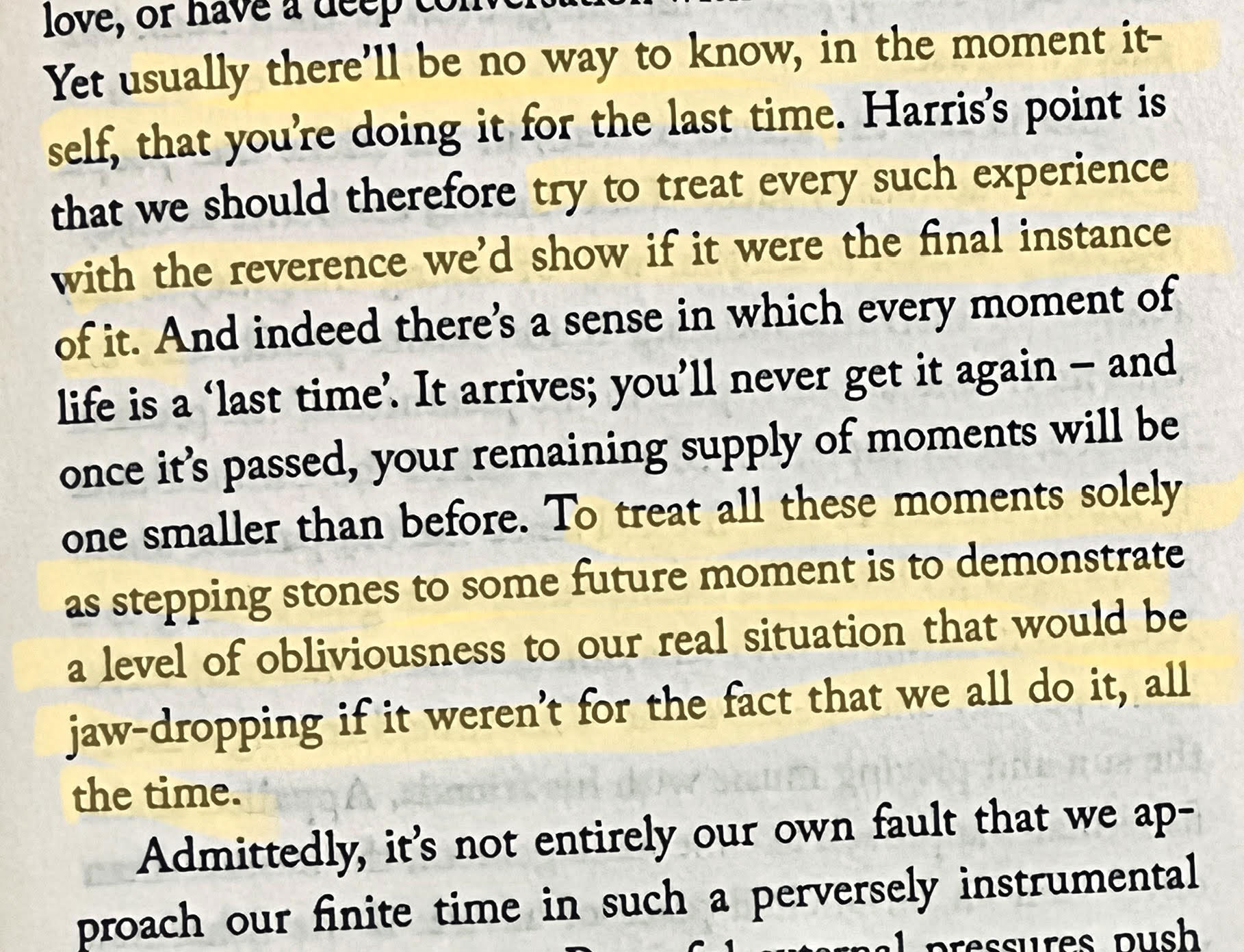

Add to this, the poignant note that we never know when something we are doing will be the last time. Here's a snippet from his book that expands on this point and suggests to all of us that we need to take more notice and joy in the mundane actions in our work and even in our daily interactions with colleagues, let alone family and friends, because we never know if we'll ever get to repeat them.

One of the things that resonated for me, apart from learning to decide to say "no" to some things, was the invitation to embrace the opposite of FOMO (fear of mission out), which is JOMO (joy of missing out). When you truly understand your finitude, you realise that some things (many things) need to be let go.

For me, one of those things was preciously guarding how I spend my attention and my care. Along with all the ludicrous and passionately-pushed conspiracy theories on my beloved social media channels (after all, I was the first person to run social media training for businesses in South Australia), there are many worthwhile causes to learn about and act upon.

But, with greater awareness of my realistic limits, Burkeman convinced me to remove the mobile phone apps for all my social accounts and actively take control of where I direct my attention; not just let the habitual, addictive "quick check" of notifications to waste that resource.

It's been liberating.

In fact, I am sure I dodged hours of "expert" and inflammatory commentary about Omicron and Novak Djokovic, and was able to be more present to my family as a result.

If you've never done a two-week stint of no social media, I can highly recommend it. And I can tell you a secret; you'll miss nothing of any consequence.

That's a sobering thought for people in the marketing game who have set themselves up to just "churn out" content for clients.

One other approach I have adopted is the simplification of my To Do lists.

There are now three columns:

- The open list for everything

- The closed list of a maximum of 10 items that I'm working on at any one time

- And the temporary list when items go when I'm awaiting input from others

I'm curious to see how this simplified approach works, especially when it's coupled with a strict maximum of one major work project and one major life project at any one time.

Changes are afoot!

A theory about finding meaning in life to help decide what's important

In Man's Search For Meaning, Viktor Frankl shares some insights borne of his time in a number of different Nazi concentration camps during WWII.

What makes Frankl's insights so worthy of respect is that his approach to helping to decide what's important was tested in the most extreme conditions of nakedness; prisoners were stripped of their clothes, stripped of their freedom, and stripped of their names (they were only ever referred to by their arbitrary prisoner number).

It's hard to find the same gravitas that Frankl delivers, when you go searching among the TikTok and Instagram teachers whose secrets to happiness involve buying certain cosmetics or choosing build-yourself furniture items.

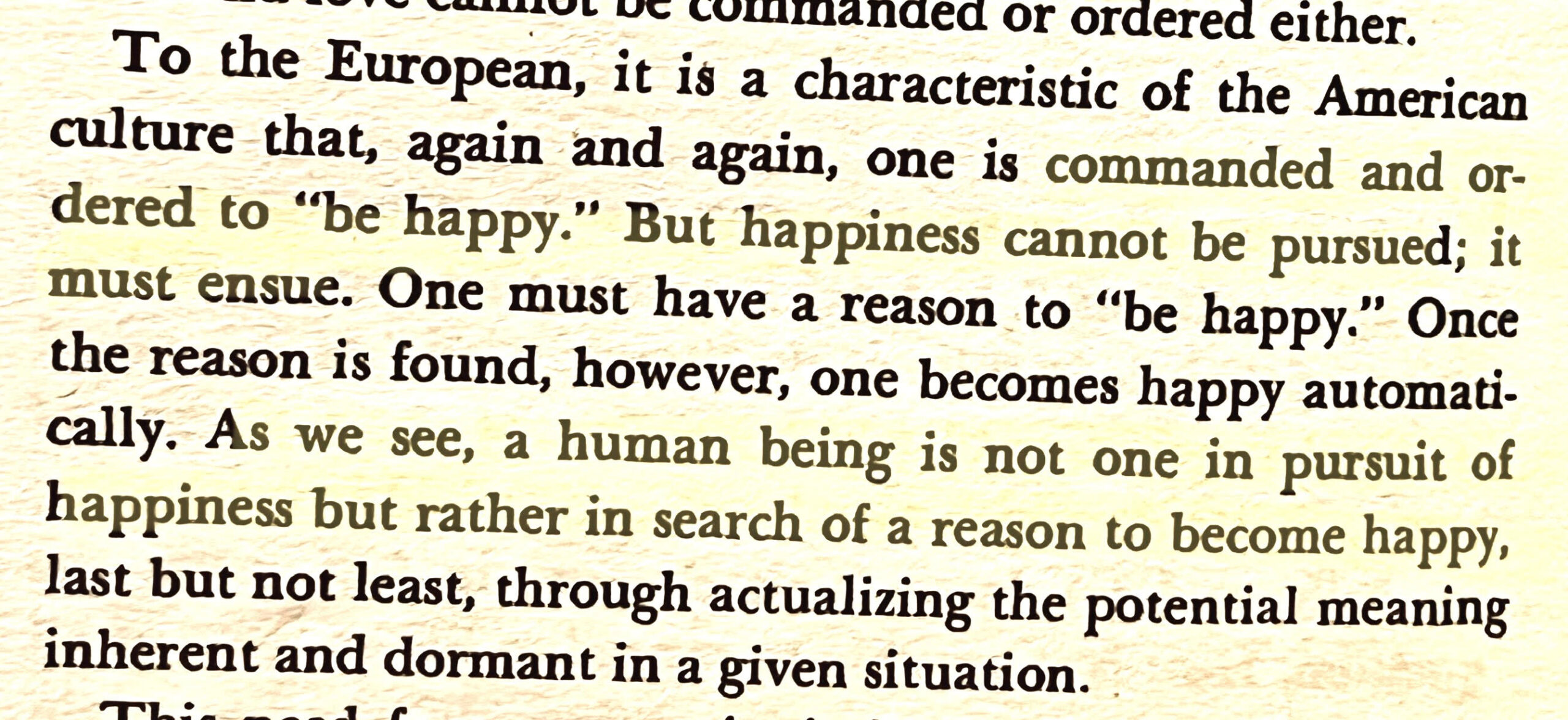

Another contrast between the "coaches" of today and Frankl, is that he saw happiness as a by product of us discovering some purpose, not as the purpose of our endeavours.

I was put onto this book by Peter Greste, the Australian journalist who was wrongfully jailed on charges of terrorism in Egypt, when I interviewed him for The Adelaide Show Podcast - hear the interview with Peter Greste here.

Peter said Frankl's book was a transformative read when all hope was lost and all control taken away. He sums up Frankl's insights eloquently, noting that:

- Looking for meaning within yourself is too fragile and self-centred to last

- Looking for meaning in a god is too abstract to really cut through

- But looking for meaning in others, in engaging with particular people or groups of people or causes - this gives a sense of purpose that can help us be resilient even when we're tested beyond our limits

Interestingly, both Greste and Frankl observe that we are all more resilient than we might think but that, luckily, very few of us have ever been truly tested.

From a business perspective, I have spoken with local business owners who have anchored their meaning and purpose in the "family" of their staff. Amid restrictions and disruptions, they have gone without, they have endured stress and hardship; often to a point beyond their wildest imaginations.

Perhaps this is a time for all of use to take a moment to place the locus of our business' meaning or purpose. Is it based on being able to keep those BMW payments up? Or is it based on supporting the various families who rely upon the supply chain or the final products and services?

Tackling imposter syndrome by observing tendances to overwork or avoidance

So far, we've looked at coming to grips with how finite our time is, and the importance of finding a locus of meaning outside ourselves or our bank balance.

While we're on a roll, now seems to be as good a time as any, to deal with another Achilles heel that affects many small business owners; Imposter Syndrome.

Imposter Syndrome is that dent in confidence we have that either robs us of the ability to appreciate our successes (or truly learn from our failures) or steers us away from opportunities for fear of being "found out".

Dr Jessamy Hibberd has written a compelling book, The Imposter Cure, which deals with this dilemma head on, using scientific theories and case studies.

I've had many business people confide in me their sense of being bogus, of not being as good as people think they are. Interestingly, this typically rises to the surface in my Blogging workshops.

The moment when we are encouraged to stick our head up and out of the trenches, to share and insight or put forward a helpful idea or argument, feelings of being an imposter rise to the surface.

Hibberd explains the many varied ways in which this insidious syndrome can rob us (and the world) of our full potential, and early on she lists some of the symptoms, with the two most common ones being:

- A propensity and drive to overwork

- A habit of avoiding true tests

They are my paraphrasing of the terms. In short, if you find yourself gravitating towards work and unable to turn off and rest, there's a great likelihood you are being driven by a horrendous need to work frantically to "prove" yourself. She is clear that hard work is good and necessary, but those of use with Imposter Syndrome take things way to far.

Avoidance is another coping strategy. By putting off a task until the last minute, the coping strategy is designed to give you an "out" if it fails. The presentation wasn't perfect? Well, you say to yourself, I was only able to start preparing at the last minute (yes, that load of washing and reordering of stationery were vital).

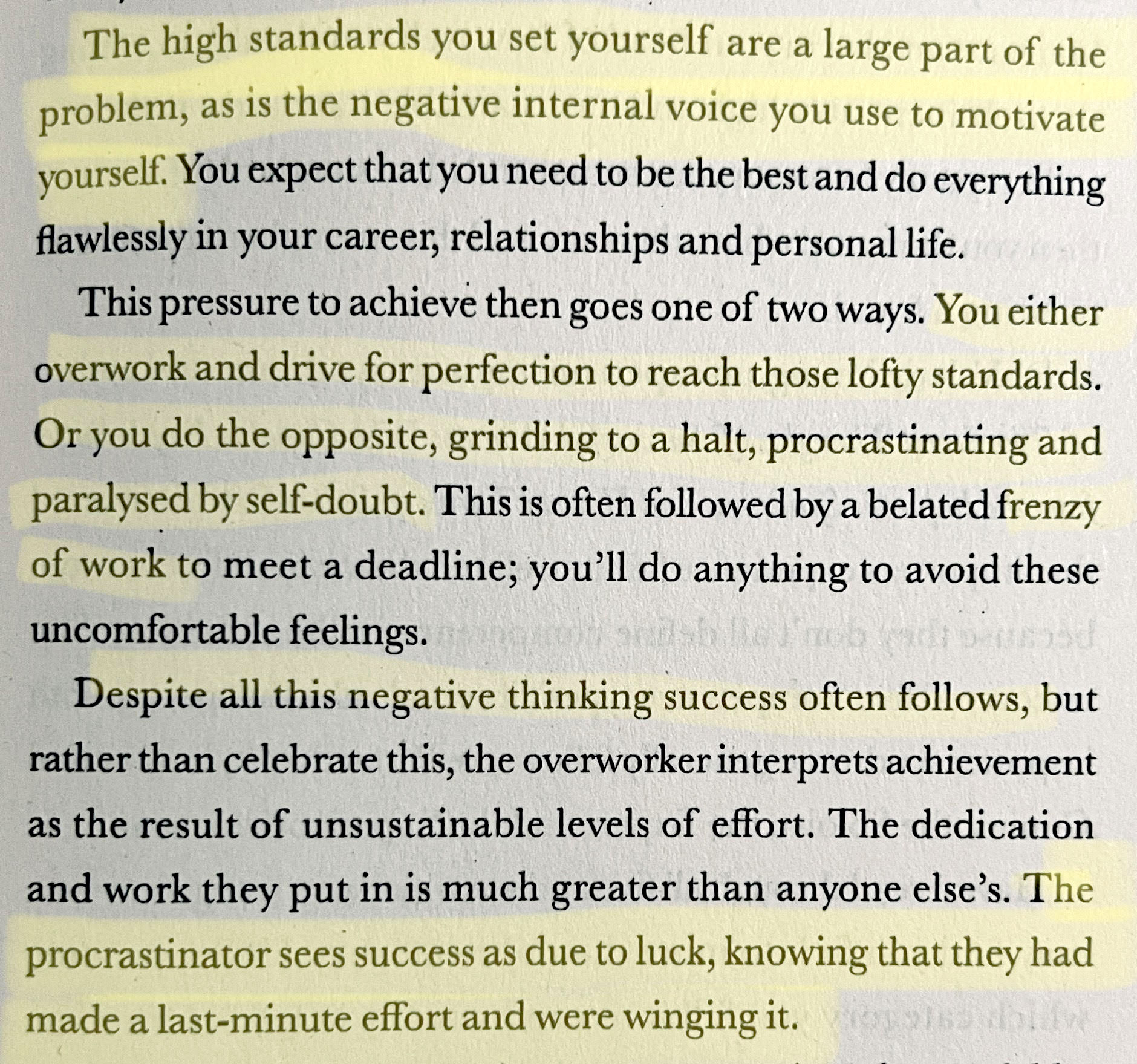

Here's a snippet from her book that expands on this idea.

Hibberd's message to us all is to notice this negative voice that tells us we have succeeded through luck, or through timing, or through someone we knew, or because people didn't notice the truth, and, instead, accept that while those elements can be in the mix, repeated successes over time show there's something about us of quality and worthiness.

Short of reading the book yourself, a key takeaway is to stay comfortable with working hard BUT within fair boundaries, even if that means settling for 80% perfection instead of 100%. Furthermore, distancing ourselves from our work can help us listen to criticism as a learning opportunity, safe in the knowledge that all great people have failed along the way.

Perhaps the final word should go to a finding that Hibberd quotes from The Top Five Regrets Of The Dying by Bronnie Ware, where number two in the list was, I wish hadn't worked so hard.

By way of leaving you with something tangible to ponder, in using January (or any time) to re-evaluate the direction of your business and decide what's important, the process of setting SMART goals seems to sit fairly within Hibberd's thinking because it applies boundaries and it sets up ways of capturing objective data to chart your progress. Here's Michael's article on setting SMART goals for business.

Happy New Year!